Investing in European equities

Is it time to invest in European markets?

Europe has not been a particularly popular place to invest in, historically, for UK investors, but some advisers are beginning to favour it for the year ahead.

Amid the economic fallout from the global pandemic, with more and more big companies in the UK - especially in retail and travel - making redundancies, investors may be looking elsewhere for their returns.

Meanwhile, the severity of the coronavirus has also widened the gap between the investment world's winners and losers of recent years.

And although Europe is not immune from the crisis, there are certain factors which could make it a viable option for investors.

In this report we examine how how attractive European equities are to investors, which sectors may survive or do well out of Covid-19, and how European equities compare to UK equities.

Advisers favour European equities for the

next 12 months

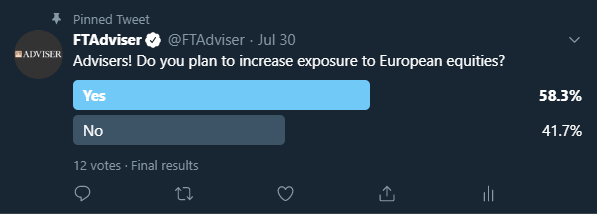

By a small majority, advisers are planning to add to their European equity exposure in the year ahead, according to the latest FTAdviser poll.

The poll showed that, by a majority of 58 per cent to 41 per cent, advisers intended to increase their exposure to European equities in the next 12 months.

The Euro Stoxx Index of European shares is down this year to date, from a starting point of 3,793 points, to the current level of 3,245.

Over the past five years, the index has fallen from 3,637 to the current level.

Flows data has been similarly negative, with investors withdrawing £451m from funds within the sector in May, compared with a net inflow of £253m into the IA UK All Companies sector in the same time period.

Tommy Faber, equity fund manager at Waverton Investment Management, said European equities have generally been out of favour with global investors in recent years, as the region is viewed as being full of companies that lack technological expertise and a desire to maximise shareholder value.

But he said while the region as a whole may have such issues, there are always individual companies within Europe that are a good investment.

Outlook for European equities

Words: David Baxter

Images: Fotoware

The severity of the coronavirus crisis has only widened the gap between the investment world’s winners and losers of recent years.

The major US tech stocks, a seemingly indestructible cohort, have only gone from strength to strength amid a shift to greater use of digital services in lockdown, while the gold price has hit a fresh record high after an already strong 2019 for the precious metal.

Government bond yields, which move inversely to prices, have remained at notably low levels.

By contrast, unloved parts of the investment universe only grew less popular when volatility struck earlier this year.

The UK equity market and sectors such as energy registered substantial falls in February and March and have tended to lag other regions and sectors as asset prices have recovered.

Bank of America Merrill Lynch’s July survey of global fund managers broadly reflects this sentiment: the research found that asset allocators were “stubbornly long” healthcare, US equities, tech, cash and bonds while remaining unconvinced about areas including energy, the UK market, banks and industrials.

European equities

But when it comes to equity regions, one market that investors have loved to hate in recent years may finally be getting another chance.

Bank of America Merrill Lynch noted a “big jump” in European equity exposure in July, while 42 per cent of respondents said they expected the Euro to appreciate.

There is evidence, admittedly of a very limited nature, that UK retail investors may be starting to feel the same way.

They put a net £41m into the Investment Association’s (IA) Europe ex UK fund sector in June.

This was only the second month of inflows from a 12-month period in which, on a net basis, investors withdrew more than £2bn from the sector.

Europe has been far from popular with investors for many years, with good reason.

Weak demographics, political issues and exposure to a variety of troubled sectors including the banking industry have all done their part to put investors off. But the region appears to have grown in stature since the coronavirus crisis began.

A good crisis?

Europe is certainly not immune from the pandemic or the economic effects of the lockdown.

Countries such as Italy have at times been notorious for their struggles in attempting to tackle the outbreak.

But some countries, such as Germany, have handled the outbreak relatively well and could be expected to show greater economic resilience.

More importantly, the European Union (EU) has responded to the crisis in a reasonably unified manner with measures that could stabilise and even bolster parts of the region in future.

Member states recently agreed on the establishment of a landmark EU recovery fund.

As part of this, the European Commission is to raise €750bn (£675.2bn) on capital markets, with €390bn (£351.1bn) of this to be distributed as grants to member states and €360bn (£324.1bn) of loans.

Europe has been far from popular with investors for many years, with good reason.

The money will be used to deal with the consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic.

This, combined with loose monetary policy, could help boost the economy in the coming years, but European equities are yet to take off significantly compared with other markets.

Performance of equities

As of 12 August, the FTSE Europe ex UK had risen by 0.7 per cent in sterling terms, according to FE data.

This puts it ahead of both the FTSE All Share, which remains in the doldrums, and Japan’s Topix.

But the European index remains behind MSCI Emerging Markets, the S&P 500 and MSCI AC Asia ex Japan.

When viewed in the context of potentially frothy prices on US equities, Europe does look appealing.

Pictet Asset Management noted in a Q3 outlook published in August that Europe appeared to be in better shape than the US, “whether the vantage point is the economy, the political landscape or Covid-19”.

Pictet added that the EU’s recovery fund and continued monetary stimulus could put the region’s economy on a firmer footing.

But the fund house stressed that much of this good news was yet to be priced in.

“Crucially for investors, Europe’s stockmarkets do not yet discount the region’s improving economic prospects, particularly when compared with their US counterparts,” the firm said.

“At current levels, the gap in US and European price to book ratios (3.7 vs 1.7) implies American corporations’ return on equity will further outpace that of European firms, widening from a differential of 5 percentage points to more than 10 percentage points.

Such an outperformance looks highly unlikely.”

Bargain hunt

European equities could therefore stand out as a cheaper complement to the likes of US stocks.

When viewed in the context of potentially frothy prices on US equities, Europe does look appealing.

On top of this, the European market’s composition sets it apart from others.

While US equity returns have been led by the tech majors, Europe has exposure to some more mature industries that could behave differently if economic conditions change.

The FTSE Europe ex UK index had a 12.4 per cent weighting to industrial goods and services at the end of July, with 8.5 per cent in food and beverages and 6.5 per cent in banks.

Europe is still home to some more fashionable sectors: healthcare represented nearly 17 per cent of the index, with pharma giants such as Roche and Novartis among the market’s biggest constituents, while tech represented around 9 per cent.

But the region’s exposure to some cyclical industries, something that has arguably held it back in recent years, could provide a boost if economic activity picks up.

It is notable that cyclical sectors such as industrials tend to do well if inflation picks up, something that could come about on the back of the huge fiscal and monetary stimulus seen this year.

Value investing

This could especially benefit those value investors who have favoured these unpopular sectors.

Lazard Asset Management recently stated in an outlook note on Europe that the discounts available in some pockets of value stocks had “reached all-time lows, relative to both their own history and the market as a whole”.

The company's outlook added: “It is starting to seem appropriate to think about these deeply valued areas of the market alongside the best compounding stocks as we move through the next phases of this economic cycle”.

However, it is important to note that an inflationary scenario does not automatically benefit all stocks viewed as value investments.

Banks, for example, tend to flourish when interest rates rises in response to inflation, but central banks could potentially keep rates low and allow inflation to run higher for some time.

Value investment strategies and cyclical stocks have also had plenty of false dawns in recent years, and it would be unsurprising if cautious investors persist with quality growth stocks.

How to invest

If investors do fall back in love with European stocks, a simple index tracker would be one way to take advantage of this momentum.

But a complication of investing in Europe has often been that while the region is home to many outstanding companies, the broader market often experiences its own problems.

If this continues, active funds might be the best bet.

This stands in contrast to the US, where active managers often struggle to beat a market whose returns are led by a handful of dominant companies that make up a huge chunk of the index.

Some, but not all, European funds have fared well this year.

As of 13 August, 56 active funds in the IA Europe ex UK sector were ahead of the FTSE Europe ex UK index year-to-date, in sterling terms.

With 120 funds in a sector that includes around 10 trackers, this means that just under half of the active funds have beaten that particular index.

In recent years, a strictly bottom-up approach has worked well, given the economic difficulties facing the region.

Miton European Opportunities, one of the best-performing names in the peer group of the last few years, has done well from a focus on high quality companies with a bias towards mid-cap names.

In a July commentary the fund’s managers noted: “We are stock pickers, not economists. We will continue to try and run an economy-balanced fund.

We won’t be selling every ‘cyclical’ and buying every ‘defensive’. A portfolio of great companies will thrive/survive whatever the weather.”

However, stockpicking can still go wrong.

Stockpicking caution

The Miton fund was among those with a position in Wirecard, the payments company that collapsed earlier this year amid allegations of fraud.

However, the fund’s managers did limit the size of their position because of concerns about the company, which contained the damage to an extent.

But a complication of investing in Europe has often been that while the region is home to many outstanding companies, the broader market often experiences its own problems.

The European Opportunities Trust, run by famed ex-Jupiter manager Alexander Darwall, had a double-digit position in the stock, only offloading the position when the scale of the problems became apparent in June and the company’s share price collapsed.

As such, some of the usual rules of fund picking do apply: diversification, either by using more than one fund in a region or by backing funds with wide exposure to different companies, sectors and countries can help limit risks, if it also limits a client’s prospective returns.

But backing well-resourced teams with a repeatable process of investing in companies that can grow independently of the wider economy has tended to work well.

This is particularly important in the context of resurgent geopolitical concerns.

The US/China trade war could be unhelpful for the region, given that European companies export plenty of goods to China.

Brexit will also once again rear its head, making life less predictable for UK and European equity markets.

In this context, allocations to Europe are unlikely to provide an easy win for investors.

But at a time when all eyes are on the best and worst of the investment universe, European equity funds could keep grinding out useful returns.

Does the surge in government borrowing matter?

Fiscal policy may be today’s saviour, but Schroders' chief economist Keith Wade thinks the massive increase in borrowing caused by Covid-19 will create significant challenges in the future.

Signs that the US recovery might be stalling in the face of a second wave of Covid-19 cases look set to draw a predictable response from Congress.

Lawmakers are putting together another rescue package, the fifth since the crisis began, which is expected to top $1trn.

Spending packages approved by Congress this year already total some $2.5trn and although not all will be spent, the budget deficit looks set to rise to $3.5trn (17 per cent of GDP) this year.

The UK story

The US is not alone. UK borrowing is expected to rise to £350bn this fiscal year, the highest nominal amount since the Second World War (WW2).

And deficits are surging across the world, with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimating that some $9trn has been put forward in fiscal support and that public debt will exceed WW2 levels for the G20 at 142 per cent of GDP in 2020.

Looking at the total debt picture for the US, it looks like we are moving into a new phase where total debt to GDP takes another significant step higher.

Within the total, IMF projections show US debt rising from 109 per cent of GDP in 2019 to 141 per cent of GDP this year.

For the Eurozone, the figures are a more palatable 84 per cent to 105 per cent of GDP; however, these include Italy where debt is expected to exceed 166 per cent GDP in 2020.

It is Germany, of course, which is keeping the average down and the figures do not include the costs of the new €750bn European recovery fund, worth 5.4 per cent of GDP for EU27 (the 27 member states remaining after the UK’s exit from the EU).

Make no mistake, these policies are a vital lifeline to people and businesses during the downturn in providing a bridge across the pandemic.

They are necessary for the economy to remain intact and able to deliver the recovery when the threat of Covid-19 recedes.

Nonetheless, they also raise questions about the long-term costs of record debt levels and the impact on the economy and investment landscape.

Are we entering a new era for debt?

Looking at the total debt picture for the US, it looks like we are moving into a new phase where total debt to GDP takes another significant step higher.

If we combine debt from government, households and business we can see three distinct periods (see chart below).

Mid 1950s to 1980

The first of these three periods saw total debt to GDP running at around 130 per cent, during which government debt levels fell while corporate borrowing rose as a share of national income.

1980 to 2000

The second phase saw an acceleration in borrowing.

The recession of the early 1980s, followed by the de-regulation of lending to the private sector, saw debt step up to 185 per cent of GDP, driven by all three sectors, particularly households.

2000 to 2020

Debt accelerated again in the first decade of the century driven by mortgage lending to households.

This was followed by the sub-prime crisis and another leg up to 250 per cent of GDP.

Between 2010 and the end of 2019, corporate debt rose, but the main driver was an increase in government debt levels.

Notably, the household sector de-leveraged during this period, such that overall debt remained steady.

The next phase: what are the implications of higher government debt?

We are now in another acceleration phase and the likelihood that the US is heading for debt levels around 300 per cent of GDP, driven by the surge in government borrowing.

One thing is clear: different sectors can leverage and de-leverage, but the overall level of debt keeps rising.

How concerned should we be about this and what are the implications?

If the economy bounces back, then tax revenues will rise and outlays fall, thus helping to bring the deficit and debt down.

This is the hope, but as the challenge of operating a business and the impact on confidence from Covid-19 become apparent, it looks less likely.

Long-run scarring effects mean there will be some permanent damage to the economy, with adverse consequences for government finances.

We are now in another acceleration phase and the likelihood that the US is heading for debt levels around 300 per cent of GDP, driven by the surge in government borrowing.

This comes on top of the extra demands on government for increased healthcare spending and infrastructure as a result of the Covid crisis - a factor we discussed in our recent update of the Inescapable Truths.

If the economy is not going to return to its previous path, the question is how sustainable will the rise in borrowing be?

Will governments be forced to take action to bring deficits down?

The role of the bond markets

In the past, the bond markets were seen as the check on government borrowing by pushing up yields on any sign of increased enthusiasm for looser fiscal policy, prompting governments to rein in their plans.

Today the bond market “vigilantes” are a distant memory and there has been little or no adverse reaction in government yields to the rise in borrowing.

This may well be due to the weakness of economic activity which has driven down inflation expectations and sent investors into safe assets such as government paper.

Such an effect would be expected to reverse as the economy recovers.

However, it could also reflect the power of central bank policy, with rate cuts, forward guidance and asset purchases driving down the cost of borrowing along the yield curve, signalling that interest rates will remain very low for many years.

Although their asset purchase programmes are in the secondary market, central banks are significant buyers of bonds and research suggests they have a marked influence on the level of yields.

The chart below shows the 10-year government bond yield in the US and the UK is at its lowest level in 120 years.

In Japan and Germany the position is more extreme: 10-year yields are negative and investors have to pay for the right to lend to these governments.

Today the bond market “vigilantes” are a distant memory and there has been little or no adverse reaction in government yields to the rise in borrowing.

Three potential problems

Why worry? After all, from an interest rate perspective there seems to be little cost from the surge in borrowing.

Helped by the action of central banks, governments are providing necessary support to the economy with interest rates at record lows.

However, looking further out we see three potential problems if high debt levels persist:

1. Central bank independence undermined

The first is the potential threat to central bank independence. Economic recovery will bring a need for tighter monetary policy to safeguard against inflation, which will push rates higher and increase borrowing costs.

Such a move will not be popular with highly indebted governments who are likely to pressurise central banks to keep policy easy.

The risk is that we see inflation pick up as the central bank is compromised in its objectives.

President Donald Trump did not hold back his displeasure at Fed tightening in 2018 and central banks generally could find it difficult to disentangle themselves from their role in helping to fund fiscal policy.

2. Savers repressed

The second is financial repression. Investors have had to cope with low interest rates ever since the financial crisis in 2008, but the latest cut in interest rates means the challenge of meeting savings targets and generating an income in retirement are even greater.

In some respects this is an objective of monetary policy: investors are being forced to take on more risk and in the process will put more savings into parts of the economy which will generate growth rather than safe assets such as government bonds.

Alternatively, investors will have to simply put more money aside to meet their goals which will reduce demand and growth in the economy – sometimes known as the “paradox of thrift”.

Either way, it means that savers have been subject to financial repression as savings returns have been reduced and the cost of a pension or other savings plan has been significantly increased.

3. Drag on future growth

The third, and probably the most significant concern, is the potential drag on future growth.

As Japan and Italy have demonstrated, high levels of public debt are associated with weak growth.

Although there is a debate about the direction of causation, there are clear headwinds on activity from high debt burdens.

The effects of high debt burdens

There are increasing financing risks to having high debt burdens.

High debt limits the ability of an economy to use fiscal policy as a tool to stimulate the cycle.

To retain the confidence of lenders, borrowers need to demonstrate that their finances are on a sustainable path and consequently find they have little room for manoeuvre on fiscal spending.

Many have to periodically tighten fiscal policy through public spending cuts or tax increases.

The recent experience of Japan is a case in point where the economy went into recession after the increase in consumption tax as the government tried (yet again) to address its long run finances.

Japan is actually one of the less vulnerable countries in this respect as financing problems are more likely in those economies which – unlike Japan – rely heavily on external funding and/or are seen as a credit risk.

Many emerging market countries fall into this category, but also developed economies such as Italy which do not control their own currency.

While investors in the current environment are searching for yield and willing to take risk, there is always the danger of a “sudden stop” in financing, which can bring a currency collapse and/or a broader financial crisis.

Growth is then impacted through a sharp tightening of monetary and fiscal policy with recession inevitably following.

The role of the dollar

The threat from higher debt can be seen in the context of the competition for funds.

Arguably the US is vulnerable in this respect by running significant budget and balance of payment deficits – the so called twin deficits.

The economy is dependent on foreign investors or “the kindness of strangers”.

As the former Governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney noted, the UK is in a similar position.

The difference with the US is that unlike the UK and others, it has the “exorbitant privilege” of the dollar, the global funding currency, so can sustain significant imbalances for longer than other less “privileged” countries.

The dollar still dominates global foreign exchange reserves, trade invoicing and lending outside the US, for example

.

Rather than a collapse in the dollar, the greater danger here is that the massive increase in US government borrowing will absorb a significant proportion of the world’s savings, creating scarcity elsewhere.

The most vulnerable in this scenario would be the emerging markets and other areas which rely on dollar funding.

Many of these economies have, of course, already faced some of the most difficult problems associated with the impact and aftermath of Covid-19 as they have simply been unable to provide the healthcare or financial support necessary to protect the population.

International organisations such as the IMF and World Bank are likely to play a greater role in ensuring that these countries remain adequately funded in the future.

The potential strain created by the US budget deficit is a form of international crowding out, where one borrower absorbs the pool of savings.

At the national level the concern is the same, with investment likely to suffer as the government crowds out the private sector.

The risk is that weak private investment hits productivity and future growth. This has been a traditional argument against high levels of government spending and borrowing and was popularised by the Reagan and Thatcher administrations of the 1980s.

However, the evidence for this is quite limited, as increases in government and corporate debt have often gone hand in hand (as the 10-year bond chart, above, highlights).

The picture today is also complicated, as the mechanism for crowding out is higher interest rates which, as we have argued, are being repressed by central banks and QE.

Nonetheless, higher government debt increases the likelihood of higher taxes, from which the corporate sector will not be exempt.

Presidential candidate Joe Biden has already made it clear that he will reverse some of the Trump cuts in corporate taxation.

High debt limits the ability of an economy to use fiscal policy as a tool to stimulate the cycle.

Private investment and productivity may also be hit by the potential return of “big government” where the government finds itself taking ownership of many key businesses but struggling as a result of support plans during Covid-19.

Conclusions

Government borrowing is rising rapidly and is likely to stay high given long-term scarring effects on the economy from Covid-19.

Even with a recovery, it is likely that governments will withdraw slowly from their increased role in the economy and some may find they hold liabilities for some time after the pandemic has faded.

The weakness of economic activity has depressed private investment and allowed the rise in government budget deficits to be financed at historically low interest rates. An outcome facilitated by central banks through ultra loose monetary policy.

However, while such a policy is needed at present and stimulus should remain in place well into next year, high government debt levels will create tensions further out.

Financial repression is putting pressure on savers who face an escalating cost of retirement.

Economic recovery will put pressure on central banks to raise interest rates creating a clash with governments who will face significantly higher borrowing costs. Central banks may find their independence challenged as a result.

There is also the danger that with many countries competing for funds we see a squeeze on those who depend on external financing or have lower credit ratings.

In particular, US government borrowing can create a scarcity of funding in more vulnerable economies resulting in retrenchment and recession as they struggle for capital.

The impact will be felt by those who have already been most affected by Covid-19.

Fiscal policy may be today’s saviour but will create significant challenges in the future.

Keith Wade is chief economist and strategist at Schroders